Foundations for Practice: The Whole Lawyer and the Character Quotient

The employment gap for law school graduates is well-documented. Almost 40% of 2015 law graduates did not secure full-time jobs requiring a law license and only 70% of 2015 graduates landed a full-time job that either required a law license or gave a preference to candidates with a juris doctor. One in four 2015 graduates did not report having any type of job, even a non-professional job, after law school.(1) The employment gap is exacerbated by another gap: the gap between the skillset lawyers want in new graduates and the skillset lawyers believe new graduates have. Only 23% of practitioners believe new lawyers have sufficient skills to practice.(2)

The gap between what new lawyers have and what new lawyers need exacerbates the employment problem, but it is even more insidious than that. When new lawyers enter the workforce unprepared or under-prepared, it undermines the public trust in our legal system. Something has to shift. And for something to shift, we had to understand exactly what new lawyers need as they entered the profession.

So we asked. In late 2014, we launched Foundations for Practice (“FFP”), a national, multi-year project designed to:

- Identify the foundations entry-level lawyers need to launch successful careers in the legal profession;

- Develop measurable models of legal education that support those foundations; and

- Align market needs with hiring practices to incentivize positive improvements in legal education.

In 2014-15, we distributed a survey to lawyers across the country. The response was overwhelming. More than 24,000 lawyers in all 50 states from a range of backgrounds and practice settings answered. Their answers are illuminating and pose opportunities and challenges to the schools that educate lawyers and the employers that ultimately hire them.

The Character Quotient

First, new lawyers need character. In fact, 76% of characteristics (things like integrity, work ethic, common sense, and resilience) were identified by a majority of respondents as necessary right out of law school. When we talk about what makes people—not just lawyers— successful we have come to accept that they require some threshold intelligence quotient (IQ) and, in more recent years, that they also require a favorable emotional intelligence (EQ). Our findings suggest that lawyers also require some level of character quotient (CQ).

The Whole Lawyer

Second, successful entry-level lawyers are not merely legal technicians, nor are they merely cognitive powerhouses. The current dichotomous debate that places “law school as trade school” up against “law school as intellectual endeavor” is missing the sweet spot and the vision of what legal education could be and what type of lawyers it should be producing. New lawyers need some legal skills and require intelligence, but they are successful when they come to the job with a much broader blend of legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics that comprise the whole lawyer.

Something for Everyone

We often think of the challenges in legal education as a law school problem. Indeed, there are steps law schools and legal educators can and must take to improve the way they educate lawyers. But law schools are not alone in their responsibility for today’s challenges, nor are they alone in their responsibility to address them. The legal profession and, notably, legal employers play a significant and often underestimated role in the perpetuation of the current system—a system with which they are disenchanted. When they fail to hire entry-level lawyers based on the skills, professional competencies, and characteristics they desire, and hire instead on traditional criteria (such as prestige of law school, class rank, and law review) they create incentives for law schools that are misaligned with the objectives toward which we all must work. Using the results of Foundations for Practice, law schools and the legal profession are empowered to join forces to tackle the greatest problems in legal education head on.

When law schools educate students toward learning outcomes developed with feedback from employers and employers hire based on what they say they want, we will see law school graduates with high character quotients who embody the whole lawyer, we will see the employment gap shrink, we will see clients who are served by the most competent lawyers the system can produce, and we will ultimately see public trust in our system expand.

Endnotes:

1. These numbers reflect long-term/full-time employment outcomes for 2015 graduates 10 months after graduation. Am. Bar Ass’n Section of Legal Ed. – Employment Summary Report, http://employmentsummary.abaquestionnaire.org/ (select 2015 class under “Compilation-All Schools Data”) [hereinafter ABA Emloyment Summary Report].

2. The BARBRI Group, State of the Legal Field Survey 6 (2015), available at http://www.thebarbrigroup.com/files/whitepapers/220173_bar_research-summary_1502_v09.pdf.

“It is a pleasant world we live in, sir, a very pleasant world. There are bad people in it, Mr. Richard, but if there were no bad people, there would be no good lawyers.”

– Charles Dickens, The Old Curiosity Shop(3)

While writers like Dickens have long maligned lawyers, the truth is that good lawyers have played a critical role in society and in the lives and businesses of the clients they serve. Yet, the question of what lawyers need to be successful—to be good—is layered in opaque complexity. Elusive though an answer to the question might seem, its pursuit is critical. It can unlock the potential to educate lawyers who are ready to begin their careers, join the profession, serve their clients, enrich their communities, and contribute to society.

Through the Foundations for Practice study, we set out to answer this question. Many before us have posited answers and we stand on their shoulders. Paul D. Cravath, of Cravath, Swain & Moore, a New York City law firm that has become synonymous with prestige and privilege, said that lawyers required traits like character, industry, intellectual thoroughness, efficiency, honesty, loyalty, and judgment.(4) More recently, small-firm lawyer Keith Lee has said that being a good new lawyer requires a “beginner’s mind,” referring to “an attitude of openness, eagerness, and lack of preconceptions when studying a subject,” and that “the universal overriding trait among exceptional lawyers is a dedication to systematic, continuous improvement.”(5) Law professor and legal market expert William D. Henderson said that “highly effective lawyers draw upon a diverse array of skills and abilities that are seldom taught, measured, or discussed during law school.”(6)

In short, we agree. Our study has confirmed the import of all of these traits and characteristics—and many more. In fact, while a study of this magnitude yields a similar magnitude of theories and paths to investigate, we have been, by far, most struck by what our study says about the importance and urgency of characteristics and, to a lesser extent, professional competencies—particularly when compared with legal skills.

The lawyers we surveyed—numbering more than 24,000—were clear that characteristics (such as integrity and trustworthiness, conscientiousness, and common sense), as well as professional competencies (such as listening attentively, speaking and writing, and arriving on time), were far more important in brand new lawyers than legal skills (such as use of dispute resolution techniques to prevent or handle conflicts, drafting policies, preparing a case for trial, and conducting and defending depositions).

The implications of this pose many opportunities for law schools, legal employers, law students, and new lawyers, which we discuss here.

Endnotes:

3. Charles Dickens, The Old Curiosity Shop (1941).

4. Robert T. Swaine, The Cravath Firm and Its Predecessors, 1819-1947, Volume 1: The Predecessor Firms, 1819-1906 266 (1946).

5. Keith Robert Lee, The Marble and the Sculptor xii (2013).

6. William D. Henderson, Successful Lawyer Skills and Behaviors, in Essential Qualities of the Professional Lawyer 60 (Paul A. Haskins, ed., 2013).

The employment gap for law school graduates is well-documented. Almost 40% of 2015 law graduates did not secure full-time jobs requiring a law license and only 70% of 2015 graduates landed a full-time job that either required a law license or gave a preference to candidates with a juris doctor. One in four 2015 graduates did not report having any type of job, even a non-professional job, after law school.(7)

Unfortunately, the employment gap runs deeper than employment rates alone. Employers lack confidence in the preparation of law graduates. In its 2015 State of the Legal Field Survey, BARBRI reported that 71% of third-year law students believe they have sufficient skills to practice, while only 23% of practitioners believe new lawyers have sufficient skills to practice.(8) In its recent report, White Paper: Hiring Partners Reveal New Attorney Readiness for Real World Practice, Lexis Nexis reported that 95% of hiring partners and associates believe recently graduated law students lack key practical skills at the time of hiring.(9)

The gap between what new lawyers have and what new lawyers need exacerbates the employment problem, but it is even more insidious than that. When new lawyers enter the workforce unprepared or under-prepared, it undermines the public trust in our legal system. Something has to shift. And for something to shift, we had to understand exactly what new lawyers need as they entered the profession.

So we asked. In late 2014, we launched Foundations for Practice (“FFP”), a national, multi-year project designed to:

- Identify the foundations entry-level lawyers need to launch successful careers in the legal profession;

- Develop measurable models of legal education that support those foundations; and

- Align market needs with hiring practices to incentivize positive improvements in legal education.

To meet the first objective, we developed a national survey to ascertain the legal profession’s perspective on the legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics (collectively, “foundations”) that new lawyers need to succeed. Then, in partnership with state bar organizations across the country and generous individuals willing to championthe effort, we administered the survey in 37 states during the fourth quarter of 2014 and the first quarter of 2015. The survey was sent to an estimated 780,694 lawyers, and a total of 24,137 attorneys—with office locations in all 50 states and representing most types of work settings and practice areas—submitted valid responses.(10)

The task of assessing Foundations for Practice is itself enormous, but we begin it with a rich vein of information. We asked respondents to rate the necessity of 147 foundations (plus two questions that allowed write-in responses); we asked fourteen questions to identify respondent demographics and practice information; we asked about the value of specialization in law school and in early practice; and we asked the respondents to identify the helpfulness of employment criteria (like law school attended, class rank, clinical experience, externships, and letters of recommendation). All of which is to say that we have a significant amount of data and countless stories to tell from that data. This is the first in a series of reports that will discuss survey results and make recommendations for implementing the results.

Endnotes:

7. ABA Employment Summary Report, supra note 1. These numbers reflect long-term/full-time employment outcomes for 2015 graduates 10 months after graduation.

8. BARBRI Survey, supra note 2.

9. Lexis Nexis, Hiring Partners Reveal New Attorney Readiness For Real World Practice 1 (2015), available at https://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/pdf/20150325064926_large.pdf.

10. For a full report on our survey methodology, see Alli Gerkman & Logan Cornett, Foundations For Practice: Survey Overview and Methodological Approach (2016), available at http://iaals.du.edu/sites/default/files/documents/publications/foundations_for_practice_survey_overview_and_methodological_approach.pdf.

With more than 24,000 responses from lawyers in all 50 states, we now have a clear picture of what lawyers need at the point they begin their legal careers. They need to have a blend of legal skills and professional competencies, and, notably, they require character. In fact, 76% of characteristics (things like integrity, work ethic, common sense, and resilience) were identified by half or more of respondents as necessary right out of law school, while just 46% of professional competencies (like arriving on time, listening attentively, and teamwork) were identified by half or more as similarly necessary. Legal skills (like legal research, issue spotting, and legal analysis) were identified by half or more of respondents as necessary right out of law school to an even lesser degree than either characteristics or professional competencies. Specifically, fewer than half of the legal skills we asked about—just 40%—were identified as necessary right out of law school. This is not to suggest that legal skills were viewed as unnecessary by respondents. In total, 98% of the legal skills we asked about were identified as necessary, but they were identified as foundations that could be acquired over time and that were not necessary as the new graduate entered his or her career.

When we talk about what makes people—not just lawyers—successful we have come to accept that they require some threshold intelligence quotient (IQ) and, in more recent years, that they also require a favorable emotional intelligence (EQ). Our findings suggest that lawyers also require some level of character quotient (CQ).

All of this suggests that successful lawyers are not merely legal technicians, nor are they merely cognitive powerhouses. The current dichotomous debate that places “law school as trade school” up against “law school as intellectual endeavor” is missing the sweet spot and the vision of what legal education could be and what type of lawyers it should be producing. New lawyers need some legal skills and require intelligence—indeed, 84% of respondents indicated that intelligence was necessary right away—but they are successful when they come to the job with a much broader blend of legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics that comprise the whole lawyer.

During survey design, we opted to divide the 147 foundations into 15 categories to create a more respondent-friendly survey experience. Analysis of the responses to each foundation by category provides an excellent lens through which to view the full survey results.

For each survey item within each of the categories listed below, we asked survey respondents to indicate whether the foundation was:

- “Necessary immediately for the new lawyer’s success in the short term” (where “new lawyer” was defined as “someone embarking on their first year of law-related work”);

- “Not necessary in the short term but must be acquired for the lawyer’s continued success over time;”

- “Not necessary at any point but advantageous to the lawyer’s success;” or

- “Not relevant to success.”(11)

Survey Categories

- Business Development and Relations

- Communications

- Emotional and Interpersonal Intelligence

- Involvement and Community Service

- Legal Thinking and Application

- Litigation Practice

- Passion and Ambition

- Professional Development

- Professionalism

- Qualities and Talents

- Stress and Crisis Management

- Technology and Innovation

- Transaction Practice

- Working with Others

- Workload Management

Business Development and Relations

Of the seven items in the Business Development and Relations category(12), the ability to retain existing business was seen as the most important foundation to have right out of law school by a fairly wide margin (38%; the next highest proportion being 17%). All but two of the foundations in this category—having an entrepreneurial mindset (45%) and engaging in marketing or fundraising activities (44%)—were seen by a majority of respondents as necessary either in the short term or to be acquired over time.

Figure 1: Business Development and Relations Responses

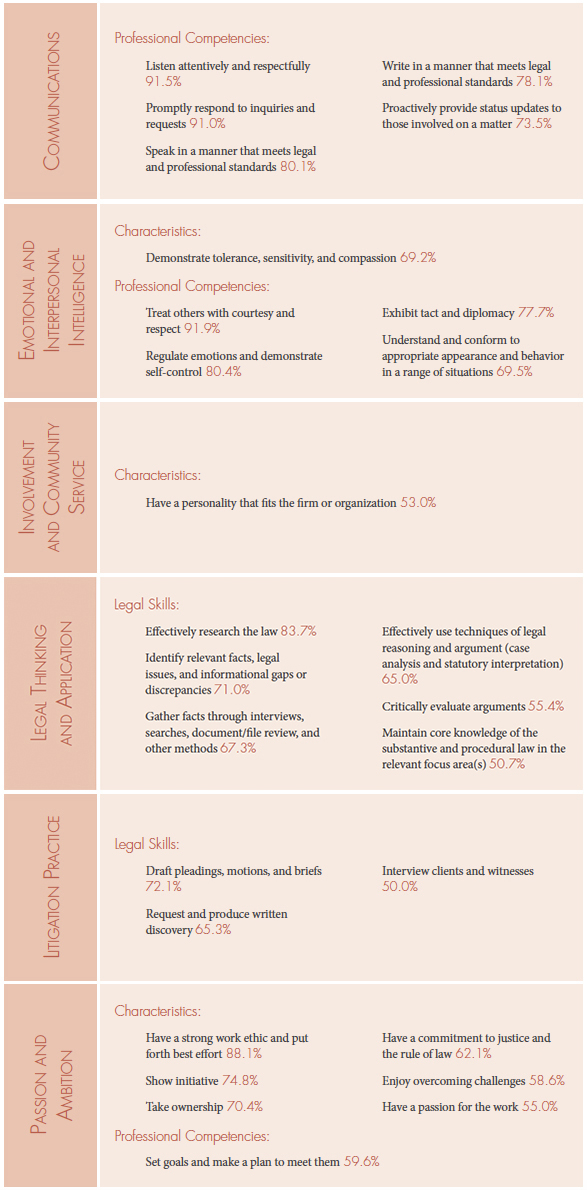

Communications

By and large, foundations in the Communications(13) category were considered necessary in the short term by a majority of respondents—with the abilities to listen (92%) and promptly respond (91%) being the foundations most often identified as such. Notably, about two-thirds (68%) of respondents considered fluency in a language other than English to be advantageous but not necessary, while about one-quarter (26%) viewed this foundation as not relevant.

Figure 2: Communications Responses

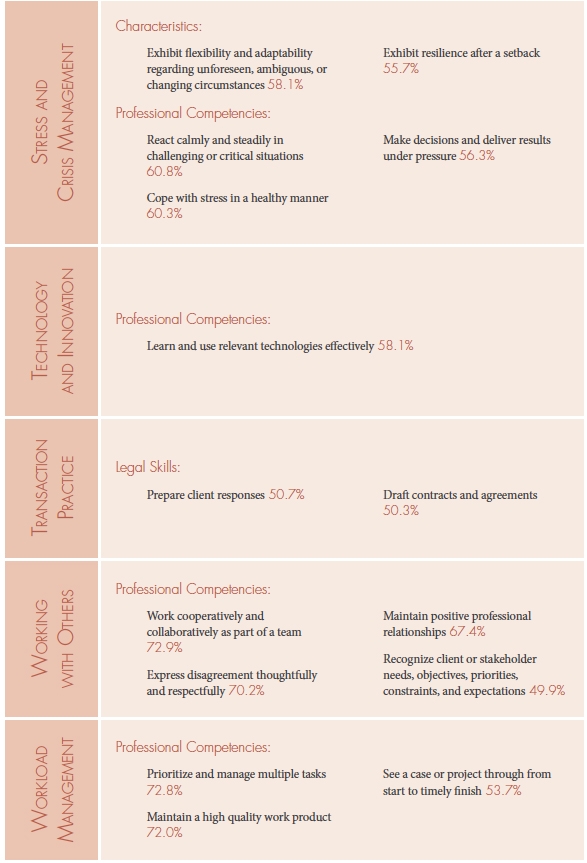

Emotional and Interpersonal Intelligence

Of the six foundations within the Emotional and Interpersonal Intelligence category(14), five were considered to be necessary in the short term by more than two-thirds of respondents. Respondents viewed the ability to treat others with courtesy and respect as the most important foundation for success right out of law school by a fairly wide margin (92%; the next highest proportion being 80%). Only 30% of respondents classified the ability to read others and understand their subtle cues as necessary in the short term, however, more than half (56%) saw it as a foundation to be acquired over time—indicating that this ability is indeed needed, but not immediately out of law school.

Figure 3: Emotional and Interpersonal Intelligence Responses

Involvement and Community Service

Respondents tended to view foundations in the Involvement and Community Service(15) category as advantageous but not necessary. This is especially true for those foundations that directly address more concrete notions of involvement: volunteer or take on influential positions in the community (56%); be involved in a bar association (56%); participate in voluntary functions or committee work at the firm (48%); and engage in pro bono legal work (47%). The more abstract foundations—maintain a work-life balance, be visible in the office, have a personality that fits the firm—were more often seen as needed either in the short term or over time.

Figure 4: Involvement and Community Service Responses

Legal Thinking and Application

There was a virtual consensus amongst respondents that the Legal Thinking and Application(16) foundations were necessary either right out of law school or should be acquired over time—very low proportions of respondents viewed these foundations as only advantageous or not at all relevant. The ability to effectively research the law was the foundation most often cited as necessary in the short term (84%); the ability to assess possible courses of action and the range of likely outcomes was the foundation most commonly identified as one to be acquired over time (63%).

Figure 5: Legal Thinking and Application Responses

Litigation Practice(17)

Of the twelve Litigation Practice foundations(18), only three were considered to be necessary in the short term by at least half of respondents: draft pleadings, motions, and briefs (72%); request and produce written discovery (65%); and interview clients and witnesses (50%). Still, respondents clearly see these foundations as important for success in practice, as all foundations in this category were identified as either necessary in the short term or to be acquired over time by at least 65% of respondents.

Figure 6: Litigation Practice Responses

Passion and Ambition

For the most part, respondents considered foundations within the Passion and Ambition(19) category to be necessary right out of law school. In fact, with one exception, a majority of respondents identified these foundations as necessary in the short term; having a passion for public service tends to be viewed as advantageous but not necessary (43%), rather than needed either in the short term or over time.

Figure 7: Passion and Ambition Responses

Professional Development

Generally, respondents tended to view foundations in the Professional Development(20) category as necessary in the short term, with taking individual responsibility for actions and results being the foundation most commonly identified as necessary right out of law school (82%). There were two marked exceptions. Almost three-quarters (74%) of respondents considered the development of expertise in a particular area as something that must be acquired over time. Authoring articles or giving presentations was seen by about two-thirds (63%) as a foundation that is advantageous, but not necessary.

Figure 8: Professional Development Responses

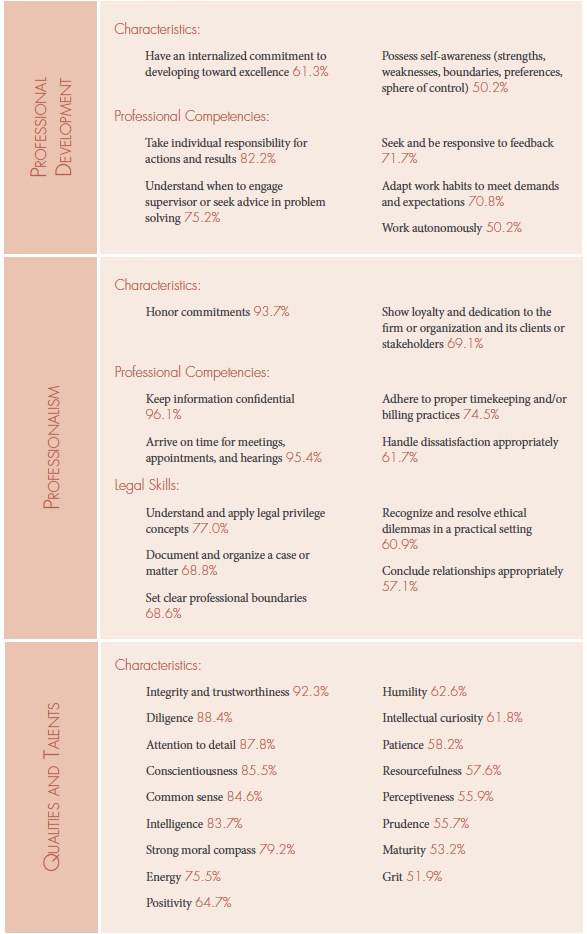

Professionalism

Within the Professionalism(21) category, the vast majority of respondents were in agreement that the foundations were necessary either in the short term or to be acquired over time. Indeed, there were three foundations which more than nine out of ten respondents identified as necessary in the short term: keep information confidential (96%); arrive on time for meetings, appointments, and hearings (95%); and honor commitments (93%). However, almost one-quarter (23%) of respondents thought adhering to proper collections practices was not relevant.

Figure 9: Professionalism Responses

Qualities and Talents

Of the twenty-four foundations in the Qualities and Talents(22) category, a considerable seventeen were considered necessary in the short term by a majority of respondents, with eight of those being considered so by more than three-quarters of respondents. Notably, none of the foundations in this category were considered not relevant by more than 4% of respondents.

Figure 10: Qualities and Talents Responses

Stress and Crisis Management

The respondents clearly valued foundations in the Stress and Crisis Management(23) category. Nine out of ten indicated all five of these foundations were needed either right out of law school or must be acquired over time.

Figure 11: Stress and Crisis Management Responses

Technology and Innovation

Three of the four Technology and Innovation(24) foundations were classified as necessary in the short term by one quarteror less of respondents; however, a majority (58%) of respondents did consider the ability to learn and use relevant technologies effectively as necessary right out of law school. Conversely, engaging in online law-related professional activity and networking was seen by a majority (52%) as advantageous, but not necessary.

Figure 12: Technology and Innovation Responses

Transaction Practice(25)

In the Transaction Practice(26) category, seven out of the thirteen foundations were viewed by a majority of respondents as abilities that must be acquired over time. There were two foundations, however, that were seen as necessary in the short term by half or more of respondents: prepare client responses (51%) and draft contracts and agreements (50%).

Figure 13: Transaction Practice Responses

Working with Others

Four of the seven foundations in the Working with Others(27) category were identified as necessary in the short term by at least half of respondents. Notably, nearly three in four respondents (73%) indicated that the ability to work collaboratively as part of a team was necessary in the short term. While generally viewed as necessary either in the short- or long-term (76%), leadership had the highest percentage of respondents indicating that it was advantageous but not necessary (22%).

Figure 14: Working with Others Responses

Workload Management

All nine foundations related to Workload Management(28) were viewed as necessary either immediately out of law school or in the first years of practice, but only three were identified as necessary in the short term by a majority of respondents: prioritize and manage multiple tasks (73%), maintain a high-quality work product (72%), and see a case or project through from start to finish (54%).

Figure 15: Workload Management Responses

Endnotes:

11. For the sake of efficiency, these options are referred to below as necessary in the short term, must be acquired over time, advantageous but not necessary, and not relevant.

12. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8963. Cronbach’s alpha allows us to estimate the internal consistency of each of the 15 categories as individual subscales within the larger survey. In other words, the higher the Cronbach’s alpha (i.e., the closer to 1), the more confident we can be that items within the category truly do measure the same construct.

13. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7159

14. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7838

15. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7735

16. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8537

17. Questions in this section were presented only to lawyers who indicated they had a litigation practice.

18. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8726

19. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7776

20. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7701

21. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8050

22. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8951

23. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8224

24. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.6883

25. Questions in this section were presented only to lawyers who indicated they had a transaction practice.

26. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8732

27. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7656

28. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7370

Foundations Types

When the profession laments the lack of preparation new lawyers have, what that preparation should comprise is somewhat surprising. Specifically, the “skills” they cite are often much broader than the typical legal skills we think of as a necessary outcome of legal education. The profession is seeking new lawyers who have legal skills, of course, but also professional competencies and characteristics. We wanted to understand just how important these broader types of foundations were for new lawyers to be successful. To do this, we divided the 147 foundations into the three types. “Characteristics” are foundations capturing features or qualities (such as sociability). “Professional competencies” are skills seen as useful across vocations (such as managing meetings effectively). “Legal skills” are those traditionally understood to be required for the specific discipline of law (such as preparing a case on appeal). Almost half (45%) of the survey items addressed professional competencies, while characteristics and legal skills each accounted for just over one-quarter of survey items (28% and 27%, respectively).(29)

Necessity and Urgency of Foundations

From a conceptual standpoint, the response options—“necessary in the short term,” “must be acquired over time,” “advantageous but not necessary,” and “not relevant”—can be thought of as getting at two different, but related, ideas: necessity of the foundation and urgency of the foundation. If a foundation is classified as either “necessary in the short term” or “must be acquired over time,” it is ultimately necessary at some point in time; the difference in these two options represents the degree of urgency for the new lawyer in gaining proficiency in the foundation. If, however, a foundation is classified as “advantageous but not necessary” or “not relevant,” clearly the foundation is not necessary for a lawyer to be successful.

Necessity within Each Foundation Type

In determining necessity and degree of urgency for the foundations within each of the three types, we considered a foundation to be necessary, advantageous but not necessary, or not relevant if at least half of respondents categorized the foundation as such. Perhaps unsurprisingly, respondents considered an overwhelming majority (92%) of the foundations to be necessary; that is, 135 out of the 147 foundations.

Within each of the three foundation types, there was some slight variation with respect to the proportion of foundations considered necessary: 98% of legal skills, 95% of characteristics, and 86% of professional competencies.(30) However, this difference was not statistically significant.(31) A small proportion of foundations were categorized as advantageous but not necessary, all of which were professional competencies (8% of foundations within that type).There were no foundations that half or more of respondents classified as not relevant, although there was a handful of foundations for which responses were more spread across the response options and, thus, no one option represented half or more of respondents (6% of professional competencies, 5% of characteristics, and 2% of legal skills).

Figure 16: Necessity of Foundations within Each Foundation Type

Urgency within Each Foundation Type

Although the foundations within each of the three foundation types—characteristics, legal skills, and professional competencies—were almost entirely considered necessary by at least half of respondents, there was considerable variation in how urgent foundations were considered within each of the types.

Overall, respondents categorized 52% of foundations (or 77) as necessary in the short term and indicated that 24% (or 35) must be acquired over time. However, there was a great deal of variation in the degree of urgency for necessary foundations within each foundation type—and these differences were found to be statistically significant.(32) Of the three foundation types, characteristics were most likely to be categorized as necessary in the short term, with a full three-quarters (76%) of foundations in that type being considered such. Much smaller proportions of professional competencies (46%) and legal skills (40%) were seen as necessary in the short term by half or more of respondents.

Figure 17: Degree of Urgency of Necessary Foundations within Each Foundation Type

Considering the data from a different vantage point, Table 1 below presents the ten individual foundations categorized as necessary in the short term by the largest proportions of respondents. Examination of these ten most urgent foundations provides further confirmation that legal skills tend to be considered less urgent than characteristics and professional competencies—in fact, legal skills make no appearance in the top ten foundations new lawyers need for success right out of law school.

Considering the data from a different vantage point, Table 1 below presents the ten individual foundations categorized as necessary in the short term by the largest proportions of respondents. Examination of these ten most urgent foundations provides further confirmation that legal skills tend to be considered less urgent than characteristics and professional competencies—in fact, legal skills make no appearance in the top ten foundations new lawyers need for success right out of law school.

Table 1: Top 10 Foundations Categorized as Necessary in the Short Term

Conversely, a closer look at the ten foundations that the largest proportion of respondents indicated must be acquired over time suggests it is legal skills that lawyers tend to think of as the foundations that should be cultivated throughout practice—and are not necessary in the short term.

Conversely, a closer look at the ten foundations that the largest proportion of respondents indicated must be acquired over time suggests it is legal skills that lawyers tend to think of as the foundations that should be cultivated throughout practice—and are not necessary in the short term.

Table 2: Top 10 Foundations Categorized as Must be Acquired Over Time

The bottom line is that—overwhelmingly—professional competencies, characteristics, and legal skills are viewed as vital to success in a career as a lawyer. The nuance lies in the degree to which these types of foundations, and the individual foundations within them, are needed immediately upon entering a legal career or can be nurtured over time. The data demonstrates that attorneys largely see characteristics as the most important foundations new lawyers need in the short term, while legal skills are necessary, but less urgent. This has valuable, and perhaps unexpected, implications for the path forward in legal education. In fact, it stands some presumptions on their head. It is not the granular, practical knowledge that new lawyers need to have in hand immediately; rather, it is the characteristics that will allow them to succeed and allow them to learn those practical skills over time. They need to show up with those characteristics, ready to learn the rest.

The bottom line is that—overwhelmingly—professional competencies, characteristics, and legal skills are viewed as vital to success in a career as a lawyer. The nuance lies in the degree to which these types of foundations, and the individual foundations within them, are needed immediately upon entering a legal career or can be nurtured over time. The data demonstrates that attorneys largely see characteristics as the most important foundations new lawyers need in the short term, while legal skills are necessary, but less urgent. This has valuable, and perhaps unexpected, implications for the path forward in legal education. In fact, it stands some presumptions on their head. It is not the granular, practical knowledge that new lawyers need to have in hand immediately; rather, it is the characteristics that will allow them to succeed and allow them to learn those practical skills over time. They need to show up with those characteristics, ready to learn the rest.

Endnotes:

29. For a full explanation of how we compiled the list of 147 foundations, see Gerkman & Cornett, supra note 10.

30. We recognize that considering a foundation necessary if at least half, that is between 50% and 100%, of respondents categorized it as such could potentially represent a great deal of variation in the actual proportions. Indeed, the proportions of respondents categorizing these foundations as necessary ranged from 52% to 99%. However, for a full 117 of these foundations, at least 75% of respondents indicated the foundation was necessary. Further, the average proportion of respondents who categorized these foundations as necessary was 87%, with negligible variation amongst the three types: 86% for professional characteristics, 89% for both characteristics and legal skills.

31. x2 (4) = 7.20, p = 0.125

32. x2 (2) = 13.17, p = 0.001

Click here to download special handout of this page information.

What emerges from the analysis of the survey responses is a clear and straightforward image of the foundations law school graduates must have as they exit law school and enter their careers. As stated at the outset, today’s new lawyers must be whole lawyers—or, lawyers with a robust mix of characteristics, professional competencies, and legal skills.

There are 77 foundations that at least half of respondents identified as necessary in the short term—or right out of law school. We believe legal educators and law schools should strive to ensure each and every law school graduate can demonstrate some level of facility with these foundations. While these foundations, listed here, are crucial, we do not intend them to limit pedagogical innovations that seek to develop other foundations that may give lawyers an advantage as they enter their careers.

Table 3: Foundations Identified as Necessary in the Short Term by at least Half of Respondents(33)

Endnotes:

33. Note that, for the Business Development and Relationships category, there were no foundations considered to be necessary in the short term by at least half of respondents.

As stated at the outset, when we started Foundations for Practice, we identified three objectives. We have achieved the first: we now know the foundations entry-level lawyers need to launch successful careers in the legal profession.

- Identify the foundations entry-level lawyers need to launch successful careers in the legal profession;

- Develop measurable models of legal education that support those foundations; and

- Align market needs with hiring practices to incentivize positive improvements in legal education.

Initially, we saw the second and third objectives as distinct, but over the last two years we have come to understand that they are inextricably linked. If we want law schools to create or sustain existing programs that educate students toward the desired outcomes identified by this study, we need employers to hire based on the foundations they said they desired; and, if we want employers to hire based on the foundations they said they desired, we need to find a way for them to buy into the school’s plan to teach and evaluate students on this broader set of learning outcomes.

For Law Schools: Measuring Learning Outcomes

Law schools are not the first institutions of higher education to think about how to better assess student learning. In a history of learning assessment that begins in the early 20th century, Richard J. Shavelson notes that “[t]oday’s demand for a culture of evidence of student learning appears to be new, but it turns out, as we have seen, to be very old.”(34) The journey has been fraught with resistance and challenges. The foreword to Shavelson’s article warns: “One of the most dangerous and persistent myths in American education is that the challenges of assessing student learning will be met only if the right instrument can be found—the test with psychometric properties so outstanding that we can base high-stakes decisions on the results of performance on that measure alone.”(35)

When it comes to assessment, American law schools no longer have the luxury of pursuing the perfect at the expense of the good. The American Bar Association’s Council to the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar passed in August 2014 revised standards that included four standards that, broadly, require publication and assessment of student learning outcomes; utilization of formative and summative assessment methods; and evaluation of the program of legal education, learning outcomes, and assessment methods.(36) The new standards will be applied to the incoming class of 2016-17.

Standard 302 prescribes some of the outcomes law schools must set and measure, including:

a) Knowledge and understanding of substantive and procedural law;

b) Legal analysis and reasoning, legal research, problem-solving, and written and oral communications in the legal context;

c) Exercise of proper professional and ethical responsibilities to clients and the legal system;

Standard 302 also leaves the schools significant room to define their own outcomes:

d) Other professional skills needed for competent and ethical participation as a member of the legal profession.

Standard 302(d) has been further explained to “include skills such as interviewing, counseling, negotiation, fact development and analysis, trial practice, document drafting, conflict resolution, organization and management of legal work, collaboration, cultural competency, and self-evaluation.”(37) It has also been further explained to allow law schools to “identify any additional learning outcomes pertinent to [their] program of legal education.”(38) The impetus to identify and measure learning outcomes and the identification of the foundations in this study creates an opportunity for law schools. Interestingly, many of the legal skills that actually are necessary right out of law school—like using techniques of legal reasoning and identifying facts and legal issues—are among the core legal skills that law schools already spend significant time developing in their students as they teach them how to think like lawyers.

For years, there have been debates between those who think graduates need to be “practice-ready” and those who believe that law school should not be a trade school—and it appears they are both right. Respondents to our survey were clear: new lawyers donot require the “nuts and bolts” immediately when they begin to practice, but they do require foundations that will allow them to build and grow over time.

Moving forward, we recommend that law schools use Foundations for Practice to:

- Work with employers and the legal community to develop measurable learning outcomes and create and reward law school programs and courses that develop the requisite characteristics, competencies, and legal skills;

- Build those courses into the curriculum;

- Encourage prospective students and law students to assess their own foundations to help them make informed decisions about whether to attend law school and to create individual learning plans that help them develop the necessary foundations through school and other opportunities, like work experience and extra-curricular activities; and

- Evaluate the current criteria for admitting students to law school and consider new criteria that paint a picture of the applicant’s characteristics and competencies beyond intelligence.

For Legal Employers and the Profession

To help law schools make meaningful use of the results of Foundations for Practice, we need to fix another gap: the gap between what the profession says it wants in new lawyers and the way the profession actually hires new lawyers. We know that legal employers tend to hire on traditional criteria—law school attended, class rank, and law review—that may tell them much about the intelligence of the job candidate but very little about the character quotient of the lawyer or about the whole lawyer. But when asked in our survey to indicate the criteria that would tell them if a job candidate had the foundations most important to them, overwhelmingly they singled out experience, including legal employment, clinics, experiential education. Law review was noted as the second to least useful criteria.(39) We will explore these results in full in a future report, but when taken together with the results presented here their implications are clear: if the profession wants law schools to prioritize these foundations in legal education, legal employers must prioritize them at every stage of hiring—from résumé review to interview to offer.

Endnotes:

34. Richard J. Shavelson, A Brief History of Student Learning Assessment: How We Got Where We Are and a Proposal for Where to Go Next 23 (2007) available at http://cae.org/images/uploads/pdf/19_A_Brief_History_of_Student_Learning_How_we_Got_Where_We_Are_and_a_Proposal_for_Where_to_Go_Next.PDF.

35. Id., at vii.

36. Am. Bar Ass’n Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools 2015-2016 §§ 301, 302, 314, 315 (2015), available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/misc/legal_education/Standards/2015_2016_aba_standards_for_approval_of_law_schools_final.authcheckdam.pdf.

37. Id. Interpretation 302-1.

38. Id. Interpretation 302-2.

39. After indicating the necessity and urgency of 147 foundations, respondents were asked “How helpful are each of the following in determining whether a candidate for employment has the qualities that you have identified above as important?” Gerkman & Cornett, supra note 10.

We no longer have to wonder what new lawyers need. We know what they need and they need more than we once thought. Intelligence, on its own, is not enough. Technical legal skills are not enough. They require a broader set of characteristics (or, the character quotient), professional competencies, and legal skills that, when taken together, produce a whole lawyer. When we value any one foundation, like intelligence, and when we value any one group of foundations, like legal skills, we shortchange not only the potential of that lawyer—we also shortchange the clients who rely on them.

For legal education to make meaningful strides, law schools and legal employers must work together. They must focus on the desired outcome—law school graduates who are ready to enter the profession—and build learning outcomes and educational and hiring models that serve that goal. When law schools educate students toward learning outcomes developed with feedback from employers and employers hire based on what they say they want, we will see law school graduates with high character quotients who embody the whole lawyer, we will see the employment gap shrink, we will see clients who are served by the most competent lawyers the system can produce, and we will ultimately see public trust in our system expand.