Foundations for Practice 2.0

Project Status: National survey complete; focus groups underway

Foundations 2.0 will update the framework, models, and resources described below.

The origin of Foundations for Practice

Most law students graduate thinking they have the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for practice, but that opinion is not shared by the profession they hope to enter or their future clients. Indeed this gap reflects that legal education does not sufficiently prepare students for practice. Not only do under-prepared lawyers undermine public trust in our legal system, but they also struggle longer and harder than they should as they try to gain footing in the legal profession.

Legal employers often exacerbate the problem: they rely on traditional indicators of success—such as class rank and law school attended—when hiring new lawyers that fail to truly assess whether a candidate is likely to succeed in their organization. Traditional hiring criteria not only reinforce and perpetuate the gap, but they also contribute to the legal profession’s status as among the least diverse professions in the United States.

Legal educators and employers must do better: the way forward is a shift to using data-driven practices based on empirical research to guide curriculum and hiring processes.

We need to move beyond traditional approaches

Traditional models of legal education and hiring present major obstacles to adopting new and improved methods. For instance, learning outcomes have never traditionally been a part of legal education, even though they are a primary feature of education in just about every other context—from kindergarten to graduate school. Indeed, medical schools had an early form of learning outcomes in the 1930s, which have been modernized over time. In law schools, the focus is on teaching rather than learning. Moreover, the U.S. News rankings in particular stultify creative spirit and disincentivize innovation in curriculum design, admissions criteria, and faculty hiring.

On the employment side, criteria for hiring new lawyers are largely confined to small sets of information, such as law school ranking, grade point average, or professional connections. For employers, hiring is not based on the candidate’s actual experience, achievement, or performance needed for development and mastery of the competencies most relevant to the employer’s practice, but on a set of prestige factors that only tenuously connect to preparedness for practice. In addition to leaving out other key indicators for success, such as practical judgment and interpersonal relationship building abilities, the traditional hiring process limits efforts to diversify the legal workforce in law firms and throughout the profession.

Changing the status quo means seeing it for what it really is: a cycle of tradition that negatively impacts lawyers, employers, clients, and society. By applying empirical research to the problems readily identified by legal educators, employers, and clients, we can evolve and expand the paths of success for all new lawyers, but especially for those who are less advantaged because of race, gender, or socioeconomic background.

In 2016, IAALS' original Foundations for Practice project developed an empirically driven framework of the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities new lawyers need, along with models to align legal education and legal hiring around it. This suite of tools offers novel and innovative means to create alignment between law schools and legal employers, and to effectively address structural problems inherent in the status quo of the legal profession.

The original Foundations for Practice survey

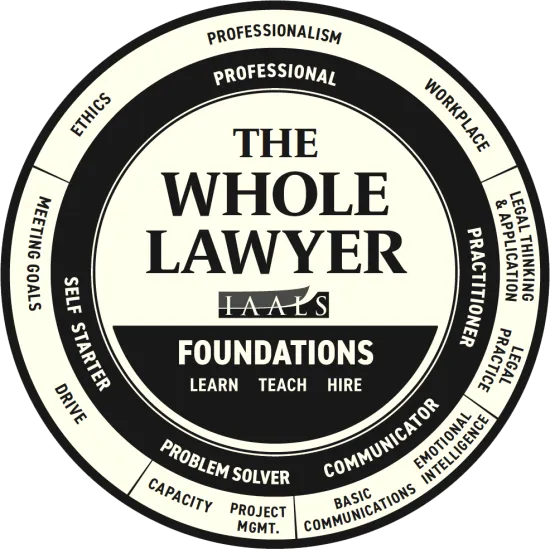

Defining the "Whole Lawyer"

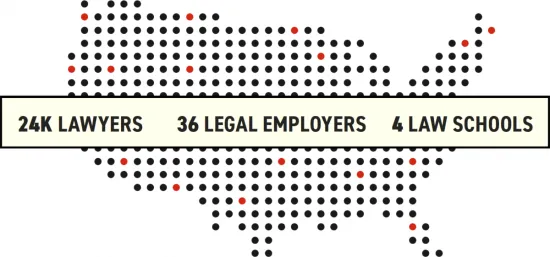

In the most comprehensive effort of its kind, IAALS surveyed more than 24,000 lawyers in 50 states—across practice settings, specialty, and geography—to uncover the essential attributes of success for lawyers as they launch their careers.

The survey asked lawyers to indicate—for their specific type of organization, specialty, or department—whether 147 different legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics are necessary immediately out of law school, can be acquired over time, are advantageous (but not necessary), or are not relevant. Ultimately, 76 items were considered necessary immediately out of law school by at least half of respondents—these are the 76 foundations a new lawyer needs to be successful.

Two findings warrant special note. First, new lawyers need character. Three-quarters of the characteristics presented in the survey were necessary right out of law school by at least half of respondents. Second, successful entry-level lawyers are not merely legal technicians, nor merely cognitive powerhouses. Any debate that places “law school as trade school” up against “law school as intellectual endeavor” misses the sweet spot of what legal education could be and what type of lawyers it should produce. New lawyers require cognitive ability and legal skills, but are most successful when they come to the job possessing 76 foundations that make up what we have termed the “Whole Lawyer”—a much broader blend of legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics.

Hiring the Whole Lawyer: Experience Matters

Our survey also asked respondents which criteria would be most helpful in determining whether a candidate for employment possesses the foundations they identified as necessary. They told us that practical experience matters. Most employers still rely on traditional criteria like class rank, law school attended, and law review. However, our respondents told us that practical experiences—such as legal employment, recommendations from judges or practitioners, participation in a law school clinic, and other experiential education—are most effective in targeting candidates who have developed some degree of mastery in the needed foundations.

Read more in our published reports to see how lawyers nationwide ranked the foundations needed for successful law practice.

Driving Change in Legal Education and Employment

Educators and employers must work in parallel to develop these essential attributes of success in new lawyers. While law schools do the important work of educating students, legal employers can influence how schools prepare new lawyers for practice by hiring candidates based on the foundations that make the Whole Lawyer, instead of a narrow set of criteria rooted only in tradition (like class rank, school attended, and law review). When employers hire new candidates based on what they actually need, they not only incentivize improvements in legal education, they also cut through bias and hire a better, more diverse workforce.

Diversity

Foundations focuses our attention on the specific abilities that make for great lawyers, enabling us to identify a wide array of experiences and achievements that build those foundations, which are not limited to traditional criteria or prestige factors that often exclude Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC). Thus, by creating more objective, transparent, and accountable practices for assessing qualified candidates for law school and for hire, Foundations has the potential to directly address systemic inequity and act as an entryway for more diversity in the profession.

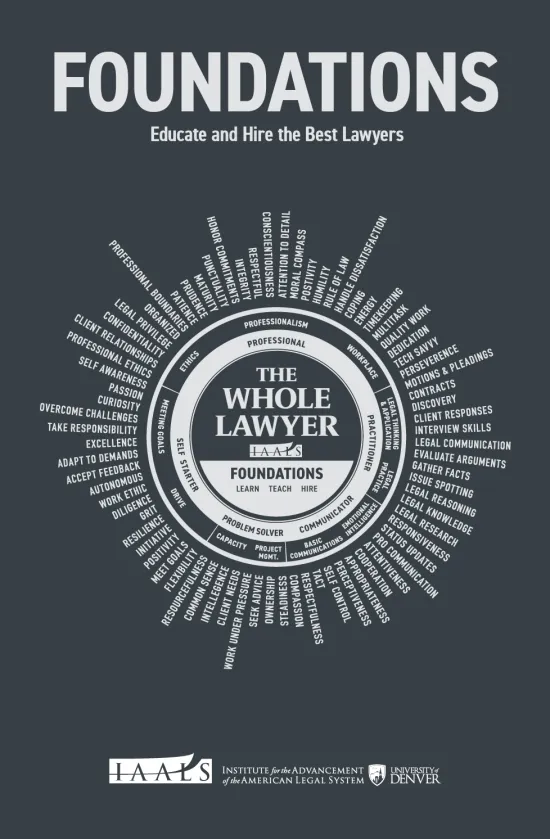

The Foundations map

To make impactful and lasting change, we used the Foundations survey results to develop a set of Model Learning Outcomes—measurable standards that describe and assess the knowledge or skills students should acquire by the end of a particular assignment, course, or program—to instill the desired characteristics, competencies, and skills in future lawyers. We then identified a team of four law schools and 36 legal employers from around the country and held interactive workshops with them through which we refined and adapted the Model Learning Outcomes, which arranges the 76 foundations into five broad categories:

- Communicator

Communicate by reading, writing, speaking, and listening in a professional manner. - Practitioner

Employ research, synthesize, analyze, and apply skills in legal processes and actions. - Professional

Use efficient methods and tools to manage one’s and the firm or organization’s professional workload with accuracy and utility. - Problem-Solver

Solve long-term and immediate problems to the benefit of all stakeholders. - Self-Starter

Demonstrate leadership, responsibility, and initiative in work responsibilities with little supervision.

The learning outcomes map

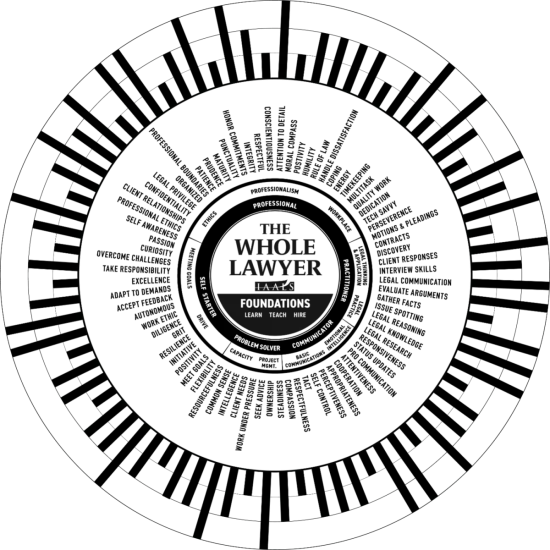

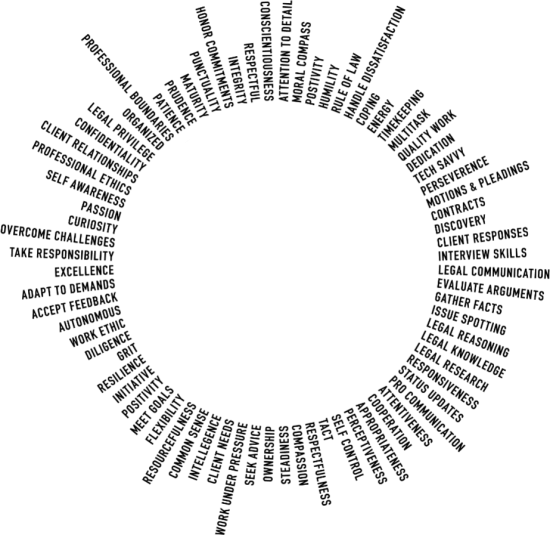

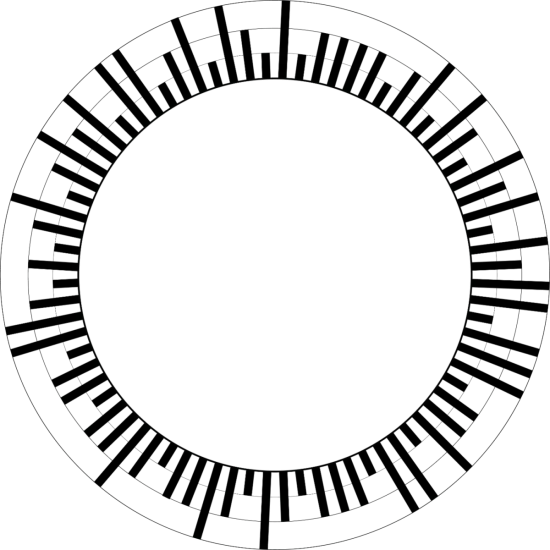

Our learning outcomes map is a visual representation of the 76 Foundations that make up the Whole Lawyer.

This model is designed to be flexible and can be used—with the assistance of the guidance, tools, and processes we developed—to measure relative mastery of these foundations. This map can be used at the individual level, with each radial reflecting a student’s or job candidate’s level of mastery of each foundation based on the length of the radial line. It can also be used at the organizational level to map the relative strengths of a curriculum or to communicate the importance of each foundation for a law school or legal employer.

Understanding the map

Five learning outcomes

The five Model Learning Outcomes in the innermost black ring serve to categorize the foundations.

Seventy-six foundations

The 76 foundations that comprise the Whole Lawyer radiate outward in the middle ring.

Measuring competency

The outer rings allow us to measure competency for each foundation across three levels—beginning, developing, mastering—according the length of the radial beams.

Partners

We identified a team of four law schools and 36 legal employers from around the country to help us refine and adapt these Model Learning Outcomes. We could not have done this work without their participation, engagement, and time.

Participating law schools

- Columbia Law School

- University of Denver Sturm College of Law

- Northwestern Pritzker School of Law

- Seattle University School of Law

Participating employers

- Akin Gump

- Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck

- Cleary Gottlieb

- Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, Chicago

- Colorado Office of Attorney General

- Colorado State Public Defender

- Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP

- Davis Wright Tremaine LLP

- Debevoise & Plimpton

- Fox Rothschild LLP

- Foster Pepper

- Fried Frank Shriver Harris & Jacobson LLP

- Gibson Dunn

- Holland & Hart

- InVigor Law Group LLC

- Jenner & Block

- Jones Day

- King County Department of Public Defense

- Kirkland & Ellis LLP

- K & L Gates

- Lighthouse eDiscovery

- Linklaters LLP

- Mayer Brown

- Molson Coors Brewing Company

- Neal Gerber Eisenberg

- New York City Legal Aid

- Ropes & Gray LLP

- Schiff Hardin LLP

- Sidley Austin

- Seattle City Attorney’s Office

- Skellenger Bender

- Starbucks Coffee Company

- The City of New York Law Department

- Wheeler Trigg O’Donnell