Public Trust and Confidence in the Legal System: The Way Forward

Over the past year, at the behest of our Board of Advisors, IAALS has examined the public’s trust and confidence in the American legal system. Many observers had already established that the public’s trust in the system is too low(1), and IAALS sought to understand why, in hopes of eventually proposing what can be done to fix the problem. IAALS consulted various thinkers who are engaged in resolving legal problems—whether in courtrooms, in law schools, or as legal counsel—and IAALS undertook our own empirical research. We held a convening, and we talked to our Board of Advisors at length. We will be rolling out the results of that process over the next few months, beginning with the three papers we publish today, which together kick off a part of the conversation IAALS calls “Are We at a Boiling Point?”

To each of these thought leaders, IAALS asked what low public confidence in the legal system means and how concerned Americans should be about its potential effects. The writers gave us three thoughtful, and often conflicting, answers. First, Professor Benjamin Barton of the University of Tennessee College of Law views the current legal climate through the lens of history, opining that our country has been in similar situations before and the rule of law has always come out on the other side intact. James Lyons, a longtime lawyer and one-time diplomat, offers the view that President Trump’s attacks on our judges and the rule of law undermine the legitimacy of the legal system in unprecedented ways. And former Chief Justice Chase Rogers of the Connecticut Supreme Court—together with her attorney co-author Stacy Guillon—write that impediments to civil court access and the polarized public discourse render the rule of law especially vulnerable to attacks coming from many sources, including state legislatures. IAALS hopes these three papers will be the start of a longer conversation, for which we will continue to offer ourselves as a venue:

-

Benjamin H. Barton: American (Dis)Trust of the Judiciary

-

James M. Lyons: Trump and the Attack on the Rule of Law

-

Hon. Chase Rogers and Stacy Guillon: Giving Up on Impartiality: The Threat of Public Capitulation to Contemporary Attacks on the Rule of Law

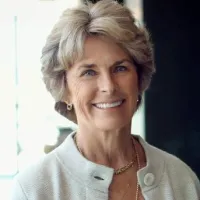

Importantly, none of these papers represents IAALS’ perspective. IAALS is apolitical, and its work is research rather than forming opinions. IAALS’ role in these papers is simply as the curator for the broader conversation. IAALS’ own contributions are its forthcoming reports on the surveys, focus groups, and interviews we conducted to better understand the public’s and attorneys’ perspectives. And, as I prepare to hand off to my successor the keys to IAALS’ mighty engine room, I here offer my own thoughts as well.

These three papers assess whether the public’s lack of confidence in the legal system poses an urgent problem and how that lack of confidence affects the rule of law in America. But the missing piece, to me, is the role the legal system itself has played in that erosion of confidence.

Indeed, when confronted with findings about the public’s low confidence in the legal system, lawyers and judges over time have devised solutions such as more civics education, more pro bono service by lawyers, and more outreach from courts to their communities. All of those solutions have merit, and I do not discount them. But they presume that the system itself is in good shape—it is just perceptions of the system that need fixing. I call this the “to know us is to love us” approach. But IAALS’ recent work, as well as the work of its peers including the National Center for State Courts, point us toward a much more profound reality: people do not trust the system because the system is not trustworthy.

The rule of law is built on the notion that the laws treat every person equally, and it holds America up as a nation in which race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and yes, even pocketbook do not affect the outcome of legal proceedings. But people do not believe that is true; hence, they distrust the legal system—and they distrust us, the lawyers and judges who populate it.

How did we get here? Let’s begin with a snippet of history. Lawyers and judges were something of a ruling class in America for generations. Following his tour of America in the 1830s, Alexis de Toqueville observed that:

In America there are no nobles or men of letters, and the people is apt to mistrust the wealthy; lawyers consequently form the highest political class, and the most cultivated circle of society. They have therefore nothing to gain by innovation, which adds a conservative interest to their nature taste for public order. If I were asked where I place the American aristocracy, I should reply without hesitation that it is not composed of the rich, who are united together by no common tie, but that it occupies the judicial bench and the bar.(2)

Lawyers also dominated Congress and state legislatures. Hence, lawyers controlled the legal system. Many questions of great public import ultimately made their way to the courts. Lawyers made the laws, enforced the laws, and interpreted the laws.

Of course, they did so under the rubric of “a guardianship mentality,” as Chris Hayes puts it in Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy.(3) Lawyers and judges take oaths that commit them to uphold the Constitution and the laws, and most states have a provision in the lawyers’ oath that provides: “I will never reject, from any consideration personal to myself, the cause of the defenseless or oppressed, or delay unjustly the cause of any person.”(4) Lawyers and judges were in charge—but benignly so. The rule of law was in our hands, and we believed that we administered it with care and a commitment to the public good. Maybe the public believed that, too.

Then, in the 1960s and ‘70s, public trust began to unravel. In the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, then the Enron scandal and savings and loan crisis in the 1980s, the subprime crisis, mortgage fraud into the 2000s, and on and on—the body politic began to lose faith in the fairness and equality of the system. That trend continues today. Increasing numbers of young Black Americans are being incarcerated, and most recently, concerns about incarceration of the poor for inability to pay court fees and fines have surfaced.(5) There is also a spilling over of mistrust of law enforcement into people’s feelings about the courts.

One sign of that loss of faith is the diminishing numbers of lawyers in legislatures and Congress. A Harvard Law School study in 2015 showed that less than 40 percent of Congress is made up of lawyers.(6) The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that at present only 17 percent of state legislators have law degrees.(7) That is a powerful insight into the public view of lawyers, and by extension, into the public view of the rule of law.

This distrust and decamping have other causes beyond the more public failures. In 2016, Rebecca Sandefur diagnosed the unmet civil legal needs of the American public and found that 80 percent of the civil legal needs of the poor go unmet.(8) On a parallel track, recent research by the National Center for State Courts shows that at least one party is unrepresented by an attorney in at least 75 percent of state court cases.(9)

Stated bleakly: lawyers and judges have failed the public. We are not accessible or affordable. As former Vice President Joe Biden put it, “the bargain has been breached . . . [t]he American people do not think the system is fair, or on the level.”(10) So, blame the politicians. Blame the insidious politicization of the judicial branch that has crept over us in the last few decades. But, at bottom, blame us.

And simultaneously, the legal profession itself is struggling. I excerpt here a portion of the Executive Summary of Professor Bill Henderson’s report to the California State Bar in July of 2018, which captures the dilemma:

…[T]he cost of traditional legal services is going up, access to legal services is going down, the growth rate of law firms is flat, and lawyers serving ordinary people are struggling to earn a living… There is ample evidence that the legal profession is divided into two segments, one serving individuals (PeopleLaw) and the other serving corporations (Organizational Clients). These two segments have very different economic drivers and are evolving in very different ways. Since the mid-1970’s, the PeopleLaw sector has entered a period of decline characterized by fewer paying clients and shrinking lawyer income. Recent government statistics reveal that the PeopleLaw sector shrank by nearly $7 billion (10.1%) between 2007 and 2012. Through this period, the number of self-represented parties in state court continued to climb. The Organizational Client sector is also experiencing economic stress. Its primary challenge is the growing complexity of a highly regulated and interconnected economy… In contrast to medical care and higher education, however, a growing proportion of U.S. consumers are choosing to forgo legal services rather than pay a higher price. The legal profession is at an inflection point.(11)

For the courts, the dilemma is evidenced not only in the numbers of self-represented litigants and the frustration those litigants feel, but also in declining caseloads. Civil litigants are taking cases elsewhere—usually arbitration or mediation—or not filing them at all. The courts are also at an inflexion point. For both lawyers and for courts, the question is: will they focus on serving the public, however and wherever they can—making whatever accommodations are necessary to provide that service? Or will they wither in a system that no longer meets the needs of that public?

In the end, I see the problem of the public’s distrust in the legal system as a problem of access to legal services and to justice. And, if that is indeed the problem, then there is a way out of this mess. We can rebuild the system in a far more open, transparent, accessible way. To do so, we have to invite disruption into our midst. We have to open up the delivery of legal services. We have to harness technology to make court processes far more accessible and understandable to people without lawyers. We have to develop robust systems that inform people about their legal rights and remedies. We have to communicate better, more reliably—to tell a story. We have to do all of those things and more.

And, at the center of each solution, we have to focus on the people using the system. We have to get their input into solutions, measure their satisfaction, ask for their help. The era of the lawyer/judge protectorate must come to an end—either gracefully or not so gracefully. To build public trust, we must recreate a system that is truly trustworthy. And, to do that, I believe we must put everyday people at the system’s center, not the lawyers and judges. Access to justice means access to understandable, accessible, and affordable legal and court services—for everyone.

IAALS is on this path, as are many other innovators and leaders around the country. Whether we are at a boiling point or not, we have a profound duty to our country, our history, and our future to assure a robust and trustworthy legal system. Innovators: your time is now.

Endnotes:

1. See, e.g., GBA STRATEGIES, NAT’L CTR. FOR STATE COURTS, THE STATE OF THE STATE COURTS, www.ncsc.org; EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 2018 EDELMAN TRUST BAROMETER ANNUAL GLOBAL STUDY 6 (2018), cms.edelman.com; DAVID ROTTMAN, NAT’L CTR. FOR STATE COURTS, PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF THE STATE COURTS: A PRIMER 2 (2000), www.ncsc.org; AM. BAR ASS’N, PERCEPTIONS OF THE U.S. JUDICIAL SYSTEM (2000), www.americanbar.org.

2. ALEXIS DE TOQUEVILLE, DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA (1835).

3. CHRIS HAYES, TWILIGHT OF THE ELITES: AMERICA AFTER MERITOCRACY (2012).

4. See, e.g., Oath of Attorney, WASH. STATE COURTS, www.courts.wa.gov/court_rules/?fa=court_rules.display&group=ga&set=APR&ruleid=gaapr05; George H. Hathaway, A Plain English Lawyer’s Oath, MICH. B. J. 434 (May 1998) (quoting the original English oath from which this language was adapted).

5. See, e.g., Monica Llorente, Criminalizing Poverty through Fines, Fees, and Costs, AM. BAR ASS’N (Oct. 3, 2016) www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/childrens-rights/articles/2016/criminalizing-poverty-fines-fees-costs/.

6. Nick Robinson, The Decline of the Lawyer Politician, 65(4) BUFF. L. REV. 657 (2017).

7. Karl Kurtz, Who We Elect: The Demographics of State Legislatures, STATE LEGISLATURES MAG.(Dec. 2015), www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/who-we-elect.aspx.

8. Rebecca L. Sandefur, What We Know and Need to Know About the Legal Needs of the Public, 67 S.C. L. REV. 443, 451 (2016).

9. PAULA HANNAFORD-AGOR ET AL., CIVIL JUSTICE INITIATIVE: THE LANDSCAPE OF CIVIL LITIGATION IN STATE COURTS (2015), www.ncsc.org/~/media/Files/PDF/Research/CivilJusticeReport-2015.ashx.

10. James Oliphant, Biden Likens Occupy Wall Street to Tea Party, Blasts BofA, L.A. TIMES (Oct. 6, 2011), https://www.latimes.com/politics/la-xpm-2011-oct-06-la-pn-biden-wallstreet-20111006-story.html (quoting Biden’s speech about the Occupy Wall Street movement).

11. WILLIAM D. HENDERSON, LEGAL MARKET LANDSCAPE REPORT (COMMISSIONED BY THE CALIFORNIA STATE BAR) (July 2018).