Regulatory Reform and Racial Justice

The death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police has sparked protests across the country, as people call for a reckoning on systemic injustice and for long-overdue change. These recent events have led to conversations around reforming not only the police, but the multiple systems in place that perpetuate inequality and inaccessibility to the rights guaranteed by the Constitution. As Rohan Pavuluri, CEO of Upsolve and a member of the Legal Services Corporation’s Emerging Leaders Council, recently explained in Law360, a “less discussed, yet still pernicious, set of policies that must change are the rules lawyers use to regulate their own profession.”

Unauthorized practice of law (UPL) rules grant lawyers a monopoly on providing legal advice, and prevent “nonlawyers” from providing any meaningful legal assistance. In most states, these rules mean that anyone other than a lawyer providing legal services can be punished—even if those services were actually helping, not harming, consumers. An imaginary divide exists between lawyer and others (as embodied in the common usage of “nonlawyer”) to describe any service provider—or other human—that isn’t a fully licensed attorney. This divide perpetuates the legal industry’s reticence to allow non-JD holders to provide legal services.

This mindset codified in the UPL rules, along with our country’s staggering racial wealth gap, have a chilling effect on Black Americans' access to the legal system, on both becoming lawyers and on accessing legal help when the need arises. And this combination all but guarantees that an incredibly small number of Black people are able to complete the legal education and pass the bar examination required to become a lawyer. (As of last year, only 5 percent of lawyers in America are Black.)

A performance gap already exists between white and minority students among standardized tests, a phenomenon contributed to by a variety of factors such as parents’ educational background and income level, the fact that standardized tests purport to test cognitive skills, and the stereotype threat. The practical effect on minority students is that standardized testing operates as a higher barrier of entry into legal education and the profession than it does for white students, with the greatest effects pronounced among Black students. One study conducted by the Law School Admission Council found that the eventual bar passage rates for Black students was 77.6 percent, the lowest of any racial or ethnic group also included in the study.

This disparity—and the growing concern over whether the bar exam actually evaluates the skills needed to successfully practice law—has taken on a new urgency. States are struggling with whether it is prudent to make hundreds of people sit in an enclosed room for a day-long exam while the country is in the midst of a serious pandemic, or whether alternatives to standardized testing (such as diploma privilege or working under attorney supervision) are all that is needed. One thing is certain, however, and that is this disparity in bar passage rates ultimately reserves the profession and its legal services only for the few who can afford to access them.

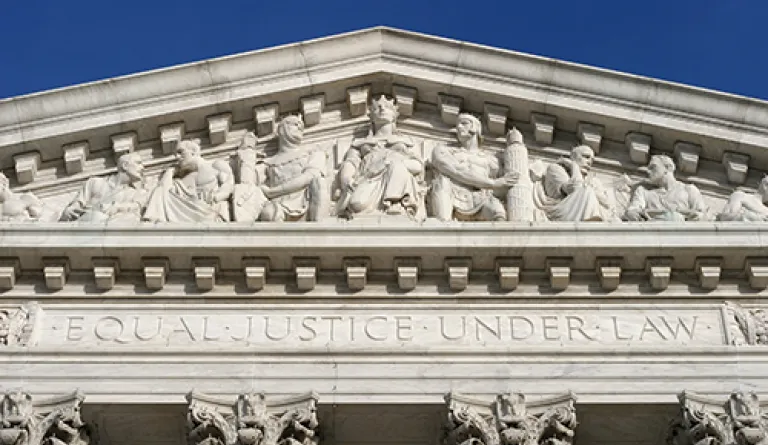

Of course, this issue does not end with legal education. The access to justice gap in the United States is well-documented and is devastating to public trust and confidence in the civil justice system—in 2017, the Legal Services Corporation published its Justice Gap Report, finding that 86 percent of the civil legal problems reported by low-income Americans received inadequate or no legal help. And this lack of accessible legal services amounts to a major power disparity, which weighs heavily on the problem of systemic racial inequity. As Pew notes, state courts today are “dominated not by cases involving adversaries seeking redress for an injury or business dispute, but rather by cases in which a company represented by an attorney sues an individual, usually without the benefit of legal counsel, for money owed.”

To take just one example, from 2010 to 2019, less than 10 percent of defendants in debt collection cases had lawyers, compared with nearly all plaintiffs—but those very few defendants with legal representation were more likely to win their case outright or reach a mutually agreed settlement with the plaintiff. And as a recent article in The New Republic lays out, “civil courts constitute a burden borne almost entirely by the most marginalized members of society. They’re poor people’s courts, Black and brown people’s courts, women’s courts.”

“Countless legal problems do not and should not require someone to pay more than $100,000 in fees to learn how to provide competent assistance,” Pavuluri writes. He suggests that social workers, paralegals, and law librarians should be trained to serve lower-income communities, in areas such as:

- Uncontested divorce

- Consumer bankruptcy

- Immigration

- Social Security disability

- Consumer debt collection

Additional efforts are underway to close the justice gap and increase the availability of legal help even more. Across the country, states are exploring ways to reform the regulation of law and reimagine how legal services are delivered. Utah is leading the way by forming a regulatory sandbox—based on IAALS’ model—that will invite new kinds of legal services and providers into the market alongside traditional lawyers for a period of time, during which IAALS and regulators will evaluate their effectiveness and any risks they might pose to the public. California is close behind; in May, the State Bar of California Board of Trustees voted to move forward with pursuing the formation of its own regulatory sandbox. IAALS, as part of our Unlocking Legal Regulation project, is supporting these efforts and others around the United States.

We must rework the rules governing legal services and we must remake the legal profession if we are to address systemic injustices. In order to open the door to Black Americans and others who have been shut out, it is imperative these efforts succeed and that courts and lawyers support these changes and increase their momentum.

“Today's UPL rules across America are a civil rights injustice. It's not hard to see why Black Americans rightfully feel like they live under a different legal system when they must overwhelmingly rely on white lawyers who they can't afford to access their basic civil legal rights,” Pavuluri concludes. “Every state supreme court and bar association has the duty to reform their UPL rules if they care about racial justice.”